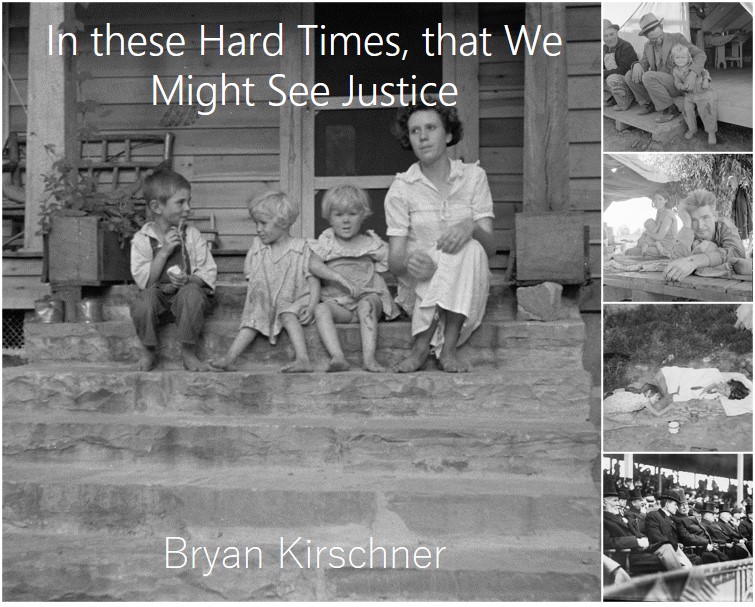

To me, the inspiration photo for Deal with the Devil perfectly suits the song.

But it didn’t initiate the songwriting process.

Rather, it was a bang-on prefect fit for the song I’d written (almost completely) at the time I went searching through photos from the Farm Security Information and Department of War Information archives.

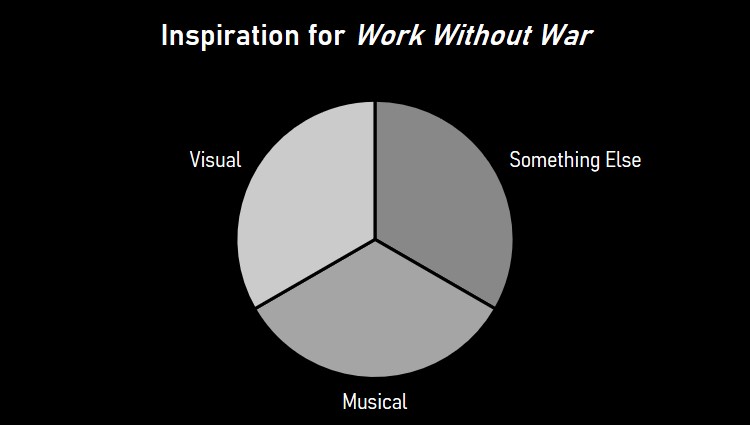

There are some very “pure” ways I proceed from “forming the intention of writing a song” to “having written a song.”

For this Hard Times Hundred & One project, one is seeing a photo and wanting to write a song inspired by it. The iconic “Jobless Men Keep Going” sign that gave rise to A Little Love, a Little Mercy was one such case.

Another is having a line or some lyrics I came up with while noodling on a concept: “They started rolling Sunday / And they ain’t slowed down / A spiritual revival wagon / Roamin’ town to town” was the genesis of The Lesson of Gethsemane. These lines were the first articulation of ideas that followed from thinking about the idea of an itinerant preacher during hard times.

Sometimes, it’s a desire to use a musical element or theme. The opening and closing chord progression of A Whole Lot of Trouble was what I found to be something in a Neil-Youngy style that I wanted to use in a song. With that in mind, I started hunting for lyrics and an inspiration photo.

Deal with the Devil started with un-directed noodling with a key (G) on guitar and seeing where it led toward tone and lyrics. “I’d make a deal with the Devil / If I could” found a nice fit with G-D-C. Ending on “C” created some tension–this wasn’t someone happy about making a deal with the Devil, this was someone in dire straits, who landed on that as his last option.

The key of “G” admitted the use of Em–I’m a fan of E minor–and after a bit of noodling around, here’s where I wound up prior to being committed to writing a song:

If you're sensing desperation, sir let's be sure we're understood I'd make a deal with the Devil, if I could ... I'll take your money Mr. Banker, though the terms they ain't no good 'Cause I'd make a deal with the Devil if I could

The former was the first refrain – the latter was the last. The storyline was about someone backed into a corner. The question at hand, if I wanted to commit to a song: what was the rest of the story?

Turns out the last part – the last stanza, where we wound up – came first:

When you’ve gone begging to your neighbors, and you’ve buttonholed your kin But there ain’t no help forthcoming, ‘cause everybody’s feeling thin You swallow your pride, hold your nose, and you pray you don’t regret Crawling hat in hand to the bankerman, and doubling down on debt I loved this final conclusion to the song. The question was: how to get there? Once I was committed to a song I faced two obstacles.

The big one was: what’s the story?

I needed a first verse to set things up, and a second to get from there to the finale.

The little one was “if I get those, I need one more refrain–a rhyming couplet. And I hate forcing rhymes. But I didn’t have anything coming to me naturally to rhyme with “could.”

Thinking about spatial metaphors was the breakthrough: the protagonist is on a journey–psychological and spiritual in nature. But what about describing it in terms physical place:

If I ain’t past the point of no return, I’m in the neighborhood/So I’d make a deal with the Devil if I could

And with that, the rest flowed.

I’ve weathered hard times more than once – but never near this bad Owing twice more than I did before, while holding half the cards I’d had There ain’t no sign of better days, fact is, things are looking worse I don’t see a chance in hell my fortunes will reverse If you’re sensing desperation, sir Let’s be sure we’re understood— I’d make a deal with Devil if I could If I could call in fifty favors or sell a golden goose I’d stop the landlord and ten creditors from tightening their noose A hundred hours of overtime would earn me hard-earned cash in hand But aint’ no men wanted here nor there, up and down this whole hard land If I ain’t past the point of no return, I’m in the neighborhood-- So I’d make a deal with the Devil if I could It’s so damn long since the good times went If I had ever dollar I that ever spent I could still use a hand from the government— And a few months of forbearance When you’ve gone begging to your neighbors, and you’ve buttonholed your kin But there ain’t no help forthcoming, ‘cause everybody’s feeling thin You swallow your pride, hold your nose, and you pray you don’t regret Crawling hat in hand to the bankerman, and doubling down on debt Yeah, I’ll take your money, Mr. Banker Though the terms they ain’t no good— ‘Cause I’d make a deal with the Devil if I could